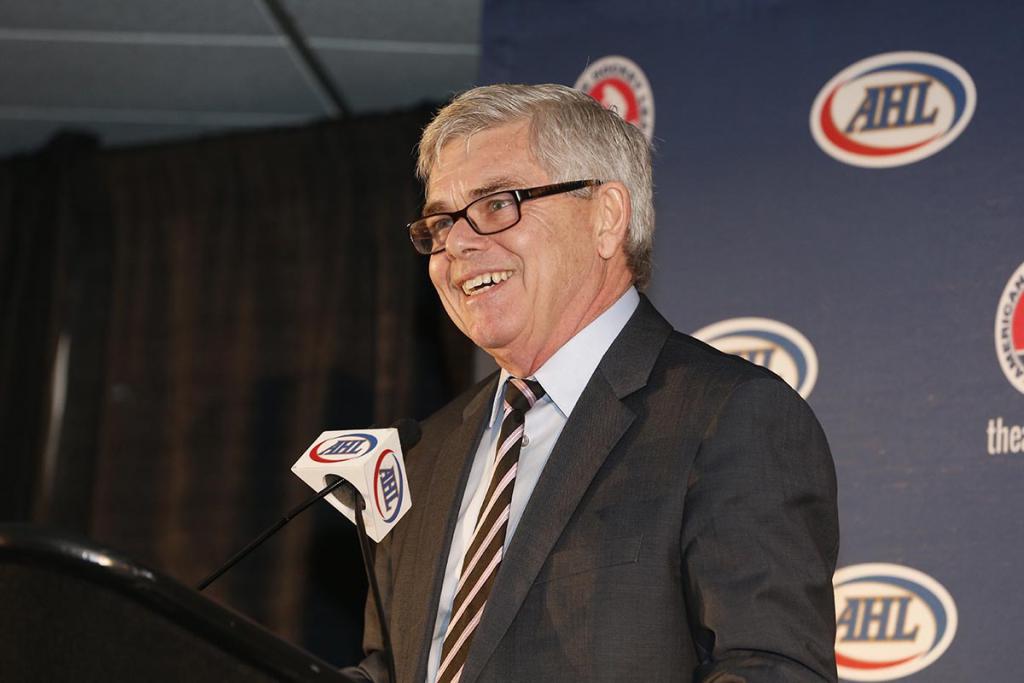

WILLIAMS: Dave Andrews leaves the AHL in a very different place; “He didn’t settle for anything less than a premier product”

Call Dave Andrews hockey’s father of modern-day player development.

Andrews took one of hockey’s top jobs when he replaced the late Jack Butterfield as president and chief executive officer of the American Hockey League in July 1994. From there he completely rebuilt hockey’s player-development model to fit the needs – and wants – of 31 NHL organizations.

In doing so, Andrews made the AHL indispensable for the NHL, something handy to have as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to bring financial challenges to every industry. He managed to accomplish that feat while also having to answer to financial realities in AHL markets ranging in size from Chicago to Utica, N.Y. That process came with plenty of headaches for Andrews, who wrapped up 26 seasons in the AHL’s top post on Tuesday.

Andrews has a few more jobs ahead of him even in retirement. He will aid in the transition for his successor, long-time NHL executive Scott Howson, and chair the AHL’s executive board. As well, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic prompted the AHL to set up the “Return To Play” task force, a group consisting of NHL general managers and AHL business-side figures. Andrews will lead that group as they work to map out strategies for the 2020-21 season.

But Andrews has been prepared for this fight, even if nobody could have predicted how the 2019-20 season would eventually end. More than a quarter-century ago, Andrews came in with a business plan, sold it to what was a very old-school league, and landed the job. He was 45 years old and fresh off seven seasons running the AHL affiliate of the Edmonton Oilers, where he had won a Calder Cup as a general manager in 1993.

A hockey background in the job is essential. But to survive, the 1990s-era AHL also needed someone with an eye for business. Today almost 90 percent of NHL players come through the AHL, as well as the bulk of coaches, officials, and executives. Those NHL prospects play in well-appointed modern facilities in a circuit occupying 15 of the 50 largest media markets in Canada and the United States.

Andrews has had to satisfy 31 NHL organizations, a contingent of independently owned clubs that are among the league’s strongest, a players association, and an ever-ranging mix of sponsors, political figures, lawyers, and other constituencies.

Bringing the AHL to that point required plenty of battles. Along the way, he and the AHL fought off the former International Hockey League on several fronts, faced pressure to build a West Coast presence, and knocked down an assortment of business challenges in an increasingly fierce battle for the entertainment dollar. Doing that laid the groundwork for an efficient development set-up that is now a must-have for NHL clubs.

“Keeping minor-league hockey structured and functioning the way it should was frankly a Herculean task that he pulled off,” long-time AHL goaltender Mike McKenna told the Around The A podcast earlier this year.

Through the eyes and experiences of those who worked with Andrews, here is how that evolution unfolded.

THE PITCH(ES)

Andrews had a good thing going in his native Nova Scotia, where his Cape Breton Oilers packed Sydney’s Centre 200 with sold-out crowds. An especially tiny base in a league filled with small ports, his Oilers thrived despite an unforgiving economy and high unemployment locally.

With a wife and three children, Andrews was not particularly looking to uproot his family again and chase hockey jobs across North America. But when Butterfield had let the league’s board of governors know that the 1993-94 campaign would be his 28th and final one, attention soon turned to Andrews. The late Macgregor Kilpatrick, the AHL’s senior vice president and general counsel, pulled Andrews aside after a meeting for a coffee. There, Kilpatrick, who had also been a team owner, pitched the job vacancy to Andrews.

Kilpatrick had a more difficult task with Andrews than he might have expected, however.

“I said, ‘Well, I don’t know that I’m electable,” Andrews recalled of the discussion. “And I’ve never even thought about it.’”

“At that time, there was kind of a rift between the Canadian-based teams and the US-based teams. Coming from an NHL[-owned] team, which in those days was in the minority, and coming from a Canadian team, was almost the kiss of death if you were trying to get the job.”

“So I said, ‘I just don’t think I’m electable based on the current sort of political climate within the league.’”

“And Mr. Kirkpatrick said, ‘That’s exactly why I want you to apply. Because we need a new look, we need a fresh look, we need a different direction.’”

That angle won over Andrews, but now he had to sell the message to Kilpatrick’s peers. The search committee eventually cut down the list to a handful of candidates and invited Andrews to interview with them in Boston.

“When I came to Boston to my interview [in 1993], I brought essentially a strategic plan for the league that I had put together,” Andrews recalled of that interview process.

“I laid it on the table and said, “If I’m your guy, this is where we’re going, and this is what it will look like. And that’s what got me the job.”

Twenty-six years later as Andrews’ tenure concluded, he could look across a much different hockey landscape. Syracuse Crunch owner Howard Dolgon brought his team into the league in 1994. While he built the Crunch into one of the AHL’s strongest franchises, he also had a front-row seat to watch Andrews’ work.

“This guy could run any league in the world and do it successfully,” Dolgon said. “He was always prepared, and he always wanted to do what was best.”

“It was always ‘What’s best for this league? How are we going to move this league forward?’”

DAY ONE

Landing a job is one thing. Doing it successfully is another order altogether. Once situated in the AHL office in Springfield, Mass., however, Andrews found himself with a massive task on his hands.

He had a 16-team circuit confined to primarily small markets across Atlantic Canada and the northeastern United States. In the summer of 1993, one year before Andrews replaced Butterfield, five of the AHL’s 15 clubs had relocated in search of more fertile opportunities.

Meanwhile, to the west sat Andrews’ main competitor, the International Hockey League. Armed with plenty of cash, cable-television contracts, major-league arenas, and markets like Atlanta, Chicago, Las Vegas, and other big-league towns — the IHL was on the march.

At stake were highly coveted NHL affiliations, markets, and the AHL’s very survival as the minor-league hockey business boomed across the United States in the mid-1990s.

Battles brewed all over the map. One club, the Worcester IceCats, played the 1994-95 season without an NHL affiliation, the last AHL club to do that. The Baltimore Bandits quickly ran into financial difficulties early in 1995-96, Andrews’ second season piloting the league. A couple of years later, the AHL and IHL each had eyes for the growing Raleigh-Durham market in North Carolina before the incoming Carolina Hurricanes eventually pushed them aside.

Shortly after the Hartford Whalers-turned-Hurricanes had left Connecticut, the same top-two minor-league circuits each circled that vacated NHL market. This time the AHL won that skirmish, placing the Hartford Wolf Pack in Connecticut’s capital city in an affiliation with the New York Rangers that still survives 23 years later.

JOB ONE – PLAYER DEVELOPMENT

Andrews had a mission to land NHL affiliations. And to win those affiliations, he needed to think with an NHL mindset. A former university goaltender before he advanced to the Western Hockey League as a head coach and general manager with the Victoria Cougars, Andrews brought hockey credentials to the job.

With that background, he knew how NHL general managers thought, what they wanted, and – perhaps even more importantly – what they did not want. Hockey is difficult enough without outside distractions. Just ask players from hockey’s many other defunct lower leagues and teams throughout the decades. They had to navigate missed paycheques, teams cutting corners on travel and accommodations, or an unwillingness to invest in player resources.

An environment like that would never suffice if the AHL was to land those NHL affiliations, especially against what the IHL could offer, and Andrews knew it. While lower leagues battled those woes, Andrews worked to ensure that such slipping standards would never creep into his league. An affable sort, he also made it clear that he ran the show. Franchises that failed to adhere to his standard heard from him.

For Andrews, his league was never “just the AHL.”

“He didn’t settle for anything less than a premier product with premier people in a premier presentation and operation,” said former San Diego Gulls executive Ari Segal.

“You could look at the AHL as minor-league hockey,” Segal said. “Or you could look at it as unmistakeably the second-best hockey league in the world. It was a constant reinforcement and celebration of the connection between the American Hockey League and the National Hockey League, and the great work that AHL teams do in their markets to grow the game at a grassroots level.”

“[It was] an undying, unending, unceasing commitment to the value of those contributions to the game of hockey.”

Hershey Bears vice president of hockey operations Bryan Helmer has seen the game as a player, coach, and executive for the AHL’s flagship franchise. A three-time Calder Cup champion, Helmer earned a spot in the AHL Hall of Fame and is the league’s all-time leader in points by a defenceman (129-435-564 in 1,117 regular-season games). He also played 146 NHL games after going undrafted.

In short, Helmer has experienced every kind of situation in pro hockey imaginable.

“Dave is very, very approachable,” Helmer told EP Rinkside last summer. “Very, very knowledgeable. He loves to talk hockey. He’s passionate about hockey, passionate about this league.”

“He has done so much for me. You know, you can call him up any time of the day. He will answer your call and be willing to give you his advice. And he’s just an incredible person. The relationships that he has made in every league, and especially with the NHL, he just has such great relationships with everybody.”

Andrews could also bridge potentially adversarial relationships.

The introduction of the “veteran rule” certainly appealed to NHL clubs’ needs and made the AHL more suitable for player development as his tenure gained speed; however, that same rule also cut into job opportunities for some of the AHL’s most established – and vocal – players. Quickly the issue became a flashpoint for talks between the AHL and the Professional Hockey Players Association.

Lawyers quickly crowded some of those initial talks between Andrews and Larry Landon, the PHPA’s executive director. The mood growing more contentious – and the legal bills piling up by the hour – Andrews and Landon eventually decided to break away from the group.

Meeting in a hotel in Albany, N.Y., then home to the wildly successful Albany River Rats club that sent a parade of future NHL stalwarts on to the parent New Jersey Devils, Andrews and Landon sorted through complicated issues and emerged with an agreement.

“I trust what Dave is going to say to me,” Landon told the Around The A podcast this past May. “There is no BS.”

McKenna, now a broadcaster with the Golden Knights, served on the PHPA player committee and took an active role in negotiations for the latest collective bargaining agreement before retiring in 2019 after 14 pro seasons.

“[Andrews] is a guy who came to our [PHPA] meetings every year and faced the music,” McKenna recounted. “One-on-one with 31 player reps, he sat there and just took questions. That takes [guts] because the guys give it to him. Afterwards, every player to a man had a newfound respect for Dave because they understand why the league has to do things [a certain way].”

THE AFFILIATION SITUATION

So, Andrews had his goal (growth and affiliations) and his methodology (a development-oriented model that contrasted with the IHL’s veteran-heavy set-up).

Now what?

In the ongoing struggle against the IHL, a protracted struggle to win NHL affiliation agreements had taken a toll on the AHL financially. Dolgon and his fellow AHL owners needed cost certainty amid these rapidly increasing costs. Earning the NHL’s trust and holding back the IHL would require a certain touch. Segal has a theory on how Andrews found a workable formula in that fight.

“It just became that Dave’s league was better suited to the development of players and hockey markets,” Segal said. “And so it created a little bit of a [repeating] cycle where it was in the NHL’s interest to work with Dave, and Dave was able to do big deals with the NHL and NHL stakeholders until it became even more in their interest to with Dave.”

“He was consistent, he was fair, he was pragmatic.”

Those traits won the AHL that significant victory in June 2001 when the IHL folded. The AHL picked off six IHL clubs, including success stories like the Chicago Wolves, Grand Rapids Griffins, Manitoba Moose, and Milwaukee Admirals. That win moved the AHL westward and set up further growth that brought the Iowa Wild and a southward push into Texas. Five of the IHL’s 17 markets from that 1994-95 season now house the AHL.

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

Geographically, the AHL’s footprint now stretches from Quebec to Southern California today.

However, the 1994-era AHL did not extend west beyond Western New York, home to the storied Rochester Americans. Now, the San Jose Barracuda are the western-most club in the AHL. Aside from that growth bringing the NHL’s top developmental league to more fans in more locations, it also enabled most NHL teams to finally realize a long-desired goal for more geographically convenient affiliations.

To build “inventory,” the AHL needed room to grow – literally. Since the 2005 advent of the NHL salary cap, every dollar counts, which often means having to shuttle players between the NHL and AHL regularly. NHL clubs eventually tired of having to shuffle players coast-to-coast. So did the players – just ask Logan Couture. As a San Jose Sharks prospect, Couture found himself jetting across the United States when the organization stationed its AHL affiliate in Massachusetts. Today the Barracuda share SAP Center and their practice facility with the Sharks, and a player recall involves a trip down the hall.

Three other AHL clubs skate in the same city as their NHL brethren, and the Laval Rocket are a quick Metro ride from downtown Montreal. Next season the Vegas Golden Knights will have their AHL affiliate 10 minutes away from the Strip when the Henderson Silver Knights begin play.

Along with the IHL clubs, the AHL also undertook a politically complicated move in 2015 that sent five franchises to the West Coast (and thereby left five cities without their AHL clubs and accelerated an exit for several New England-based clubs). A failure to execute that move could have cost the NHL affiliations. Andrews revived the AHL All-Star Game in 1995, and the league worked to strengthen itself on the business, marketing, and sales fronts.

But that shuffling came with significant upheaval, some of it painful at times.

A desired push into the US Southeast failed to take hold early in Andrews’ tenure. The AHL never could figure out how to make Baltimore work, where they had maintained a rare big-city presence in the 1980s and 1990s. Teams retreated from Atlantic Canada, eventually leaving the league without a presence in what had been a stronghold. Philadelphia, a smashing success for several years, left after the Spectrum closed. Well-supported clubs in Houston (building availability) and San Antonio (a franchise sale) departed the AHL.

Andrews was willing to take calculated chances if it meant ultimately growing his league.

“We just needed more, we needed more markets, we needed more inventory,” Andrews explained. “Yeah, they may not succeed or may not succeed long-term, but we needed homes for NHL teams to put their players in.”

In 1994-95, 16 of the 26 NHL teams had AHL affiliations. The AHL has grown from those 16 clubs to 31 teams during his tenure; 12 cities from that 1994-95 season are long gone, mainly scattered to the Canadian Hockey League, ECHL or without hockey altogether. Only four teams remain from the 1994-95 campaign – the Providence Bruins, Hershey, Rochester, and Syracuse. Of the 31 current affiliation agreements, only the Boston Bruins-Providence marriage has lasted throughout Andrews’ 26 seasons.

THE PERSONAL TOUCH

Hockey is a business built on relationships, and Andrews understood that.

“He was always able to find common ground,” Dolgon explained. “I think that is why people respected him.”

Segal, now the CEO of Immortals Gaming Club, got an up-close look at how Andrews worked. As West Coast NHL teams began to explore bringing their AHL affiliates closer to home, the Anaheim Ducks tasked Segal with digging into the AHL further. Segal started attending AHL business functions and assessing whether setting up an AHL club nearby might work for the Ducks.

“Given [hockey] politics, [Andrews] could have treated me as a mole or interloper or someone to be feared,” Segal said.

“At the time, I was a grad student. I had no credibility in hockey, and no one knew who I was, no one needed to give me the time of day. But Dave very graciously included me in everything. He let me sit in on every meeting, excluding executive sessions, of course. He included me at all the social events. He introduced me to so many people, even people that I have relationships with to this day.”

“Dave set up conversations so that I could really dig in, because I was trying to do research on the league and if it was something we wanted to invest in and be part of. [That ranged] from Brian Burke and Julien BriseBois to [AHL executives]. NBA business guys to hockey lifers.”

Those talks went well enough that the Ducks eventually brought pro hockey back to nearby San Diego, where Segal became president of business operations for the Gulls, and the team quickly became one of the top draws in the AHL. Later he became chief operating officer for the Arizona Coyotes.

“As I started coming back for [league meetings], as I started going back year after year, I think I became a friend, my wife started joining me, and [Andrews] took time to get to know her and introduce her to people’s families,” Segal said. “Dave wasn’t just empathetic when you were across the negotiating table; he just really cared about the people that he was working with.”

“And he was very proud of the American Hockey League and wanted to share that with folks. That was a very contagious energy to want to be around and be a part of.”

In a business brimming with strong, hard-nosed personalities, Andrews also possessed a disarming sense of humour that could diffuse tense meetings.

“He has real credibility on every side of every aisle,” Segal said. So, whether it was whether it was hockey folks or business people, they both felt represented and that he genuinely understood and empathized with their interests, whether it was someone coming at it from the NHL side or the ECHL. I think a huge part of the way that he led was really through empathy with all sides, number one.”

“Number two, the culture that he built as the lead was very strong and very familial. So he surrounded himself with quality people. He built very special relationships with personnel. And so when you have that kind of familial atmosphere, an atmosphere of trust and collaboration, the conditions are ripe for success.”

Said Dolgon, “This was way more than a job to him. You always had the confidence that it was going to work out.”